Would you like to live longer AND better?

The question is what “Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity” by Peter Attia is about. Attia is a Canadian – American physician who built up quite a reputation on longevity. He starred in documentaries related to how to live longer and more healthily, including Limitless with Chris Hemsworth. From a credibility standpoint, he has it.

The book looks at the four horsemen – the four main causes of health deterioration and death, such as cancer, heart disease, neurodegenerative disease or type-2 diabetes and metabolic dysfunction. Then, the author goes deep into certain topics that are related to each theme. Readers will learn about the importance of eating/eating less, exercise, mental health, sleep and so on.

I found Attia’s work informative and helpful since longevity is one of my priorities. He strove hard to draw findings and lessons from data and science objectively, to minimize confirmation bias. Some passages were refreshing to read such as the part when he talked about the difference between meat protein and plant-based protein. For the most part, the author managed to break down complex issues into layman’s terms; which is always appreciated. However, there is an overload of information. The book should have been a lot shorter with a lot of fat to cut, no pun intended. That’s pretty much the only criticism I have on Outlive.

If you are interested in being a great shape at old age, this book will be useful. Like the author said himself, even if you gain just a little bit more motivation to work out every day, that’s already a win.

“Studies of Scandinavian twins have found that genes may be responsible for only about 20 to 30 percent of the overall variation in human lifespan. The catch is that the older you get, the more genes start to matter. For centenarians, they seem to matter a lot. Being the sister of a centenarian makes you eight times more likely to reach that age yourself, while brothers of centenarians are seventeen times as likely to celebrate their hundredth birthday, according to data from the one-thousand-subject New England Centenarian Study, which has been tracking extremely long-lived individuals since 1995”

“The short answer is that evolution doesn’t really care if we live that long. Natural selection has endowed us with genes that work beautifully to help us develop, reproduce, and then raise our offspring, and perhaps help raise our offspring’s offspring. Thus, most of us can coast into our fifth decade in relatively good shape. After that, however, things start to go sideways. The evolutionary reason for this is that after the age of reproduction, natural selection loses much of its force. Genes that prove unfavorable or even harmful in midlife and beyond are not weeded out because they have already been passed on”

“One of the liver’s many important jobs is to convert this stored glycogen back to glucose and then to release it as needed to maintain blood glucose levels at a steady state, known as glucose homeostasis. This is an incredibly delicate task: an average adult male will have about five grams of glucose circulating in his bloodstream at any given time, or about a teaspoon. That teaspoon won’t last more than a few minutes, as glucose is taken up by the muscles and especially the brain, so the liver has to continually feed in more, titrating it precisely to maintain a more or less constant level. Consider that five grams of glucose, spread out across one’s entire circulatory system, is normal, while seven grams—a teaspoon and a half—means you have diabetes. As I said, the liver is an amazing organ.”

“Fat also begins to infiltrate your abdomen, accumulating in between your organs. Where subcutaneous fat is thought to be relatively harmless, this “visceral fat” is anything but. These fat cells secrete inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha and IL-6, key markers and drivers of inflammation, in close proximity to your most important bodily organs. This may be why visceral fat is linked to increased risk of both cancer and cardiovascular disease.”

“It doesn’t take much visceral fat to cause problems. Let’s say you are a forty-year-old man who weighs two hundred pounds. If you have 20 percent body fat, making you more or less average (50th percentile) for your age and sex, that means you are carrying 40 pounds of fat throughout your body. Even if just 4.5 pounds of that is visceral fat, you would be considered at exceptionally high risk for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, in the top 5 percent of risk for your age and sex. This is why I insist my patients undergo a DEXA scan annually—and I am far more interested in their visceral fat than their total body fat.”

“Lots of people like to demonize fructose, especially in the form of high-fructose corn syrup, without really understanding why it’s supposed to be so harmful. The story is complicated but fascinating. The key factor here is that fructose is metabolized in a manner different from other sugars. When we metabolize fructose, along with certain other types of foods, it produces large amounts of uric acid, which is best known as a cause of gout but which has also been associated with elevated blood pressure. Other mammals, and even some other primates, possess an enzyme called uricase, which helps them clear uric acid. But we humans lack this important and apparently beneficial enzyme, so uric acid builds up, with all its negative consequences”

“Why is protein so important? One clue lies in the name, which is derived from the Greek word proteios, meaning “primary.” Protein and amino acids are the essential building blocks of life. Without them, we simply cannot build or maintain the lean muscle mass that we need.”

“Unlike carbs and fat, protein is not a primary source of energy. We do not rely on it in order to make ATP, nor do we store it the way we store fat (in fat cells) or glucose (as glycogen). If you consume more protein than you can synthesize into lean mass, you will simply excrete the excess in your urine as urea. Protein is all about structure. The twenty amino acids that make up proteins are the building blocks for our muscles, our enzymes, and many of the most important hormones in our body. They go into everything from growing and maintaining our hair, skin, and nails to helping form the antibodies in our immune system. On top of this, we must obtain nine of the twenty amino acids that we require from our diet, because we can’t synthesize them.”

“The first thing you need to know about protein is that the standard recommendations for daily consumption are a joke. Right now the US recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for protein is 0.8 g/kg of body weight. This may reflect how much protein we need to stay alive, but it is a far cry from what we need to thrive. There is ample evidence showing that we require more than this—and that consuming less leads to worse outcomes. More than one study has found that elderly people consuming that RDA of protein (0.8 g/kg/day) end up losing muscle mass, even in as short a period as two weeks. It’s simply not enough.”

“How much protein do we actually need? It varies from person to person. In my patients I typically set 1.6 g/kg/day as the minimum, which is twice the RDA. The ideal amount can vary from person to person, but the data suggest that for active people with normal kidney function, one gram per pound of body weight per day (or 2.2 g/kg/day) is a good place to start—nearly triple the minimal recommendation.”

“If you choose to get all your protein from plants, you need to understand two things. First, the protein found in plants is there for the benefit of the plant, which means it is largely tied up in indigestible fiber, and therefore less bioavailable to the person eating it. Because much of the plant’s protein is tied to its roots, leaves, and other structures, only about 60 to 70 percent of what you consume is contributing to your needs”

“Some of this can be overcome by cooking the plants, but that still leaves us with the second issue. The distribution of amino acids is not the same as in animal protein. In particular, plant protein has less of the essential amino acids methionine, lysine, and tryptophan, potentially leading to reduced protein synthesis. Taken together, these two factors tell us that the overall quality of protein derived from plants is significantly lower than that from animal products.”

“These are great if you have the time to comb through databases all day, but for those of us with day jobs, Layman suggests focusing on a handful of important amino acids, such as leucine, lycine, and methionine. Focus on the absolute amount of these amino acids found in each meal, and be sure to get about three to four grams per day of leucine and lycine and at least one gram per day of methionine for maintenance of lean mass. If you are trying to increase lean mass, you’ll need even more leucine, closer to two to three grams per serving, four times per day.”

“Cancer cells are different from normal cells in two important ways. Contrary to popular belief, cancer cells don’t grow faster than their noncancerous counterparts; they just don’t stop growing when they are supposed to. For some reason, they stop listening to the body’s signals that tell them when to grow and when to stop growing.”

“The second property that defines cancer cells is their ability to travel from one part of the body to a distant site where they should not be. This is called metastasis, and it is what enables a cancerous cell in the breast to spread to the lung. This spreading is what turns a cancer from a local, manageable problem to a fatal, systemic disease.”

“The first such hallmark is the fact that many cancer cells have an altered metabolism, consuming huge amounts of glucose. Second, cancer cells seem to have an uncanny ability to evade the immune system, which normally hunts down damaged and dangerous cells—such as cancerous cells—and targets them for destruction. This second problem is the one that Steve Rosenberg and others have been trying to solve for decades.”

“And if exercise is not a part of your life at the moment, you are not alone—77 percent of the US population is like you.

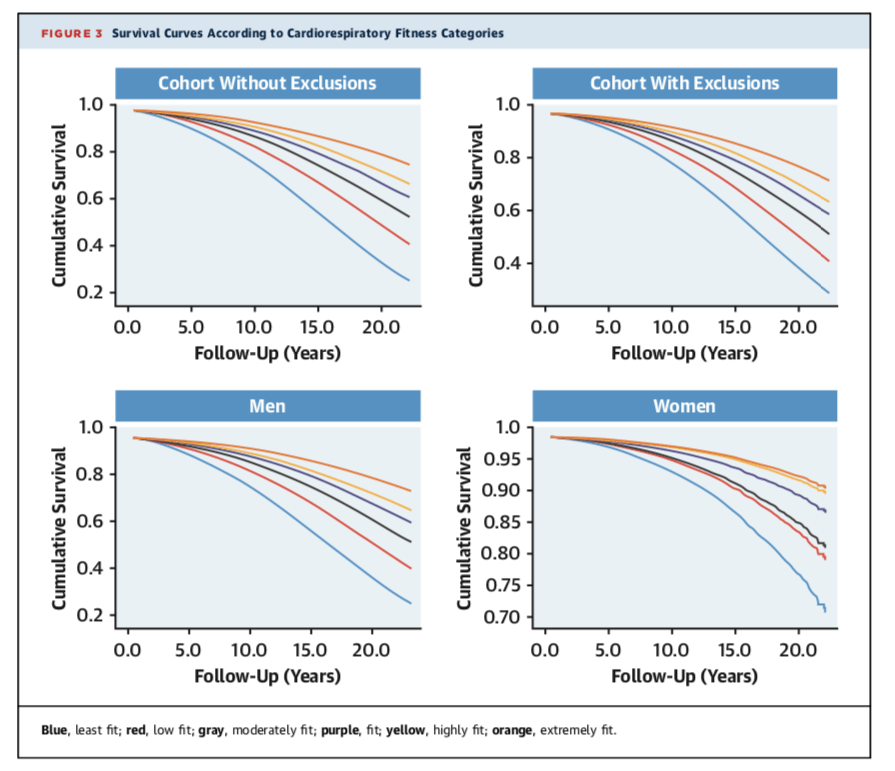

It turns out that peak aerobic cardiorespiratory fitness, measured in terms of VO2 max, is perhaps the single most powerful marker for longevity. VO2 max represents the maximum rate at which a person can utilize oxygen. This is measured, naturally, while a person is exercising at essentially their upper limit of effort. (If you’ve ever had this test done, you will know just how unpleasant it is.) The more oxygen your body is able to use, the higher your VO2 max.

Studies suggest that your VO2 max will decline by roughly 10 percent per decade—and up to 15 percent per decade after the age of fifty. So simply having average or even above-average VO2 max now just won’t cut it. We are planning for you to live for another thirty years, or forty. If you are only starting at 32 ml/kg/min now, at fifty, you can expect to be closer to 21 ml/kg/min at age eighty

If you are a man in your sixties and you are starting with a VO2 max of 30, you are more or less average for your age group (see figure 12). (Women typically have a somewhat lower average VO2 max by age, because of various factors, so an “average” woman in her sixties would be at about 25 ml/kg/min.) If you can boost that up to 35 via training, you will be squarely in the top 25 percent of your age group.”

Leave a reply to My 2023 – Minh Quang Duong Cancel reply